|

|

- Search

| Qual Improv Health Care > Volume 29(2); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Fire response education is critical for healthcare providers working in hospitals to ensure a safe environment for patients and staff. However, a comprehensive review that thoroughly examines the contents, methodologies, and outcomes of fire response education in hospitals is currently lacking.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review by adhering to the framework proposed by Arksey and O'Malley. We searched five electronic databases for literature published after 1990, using the key categories of "hospitals," "fires," and "education." As a result, we identified 15 relevant articles that met our inclusion criteria for the review.

Results

Of the 15 articles, 12 had adopted a quasi-experimental design and the remaining 3 had employed a true experimental design. The majority of these studies (11 out of 15) were conducted in the United States, with 4 studies forming committees or teams dedicated to education. Simulation methods were used in 13 studies, while 2 studies had employed a combination of methods. All studies focused on first-response procedures based on RACE (Rescue, Alarm, Contain, Extinguish/Evacuation). Outcome measures included the learners’ overall experience, performance in the educational settings, and performance in the field, with all studies reporting positive results following the educational interventions.

화재는 중요한 안전문제로 인식되는데, 특히 병원 내 화재는 병원이라는 특수한 환경으로 인해 더욱 큰 관심을 요구한다. 미국화재예방협회(2017)의 보고서에 따르면, 2011년 이후 의료시설 화재는 증가추세에 있으며, 이로 인해 연평균 2명의 민간인 사망, 157 명의 민간인 부상, 540 억 달러의 직접 재산 피해가 발생한 것으로 나타났다[1]. 국내의 경우, 국가화재통계시스템의 분석에 의하면 의료기관의 화재발생 추이 및 인명 피해는 감소세에 있으나 재산피해는 줄어들지 않고 있으며[2] 2018년 밀양 세종병원 화재, 2022년 이천 열린의원 화재 등 다수의 사망자가 발생한 화재들이 꾸준히 발생하고 있다. 병원은 구획 내 인구 밀집도가 높고 재해 약자들의 이용이 많으며, 가연물과 화기취급시설이 있는 특수성으로 인하여 화재에 대한 위험성이 높다. 환자 안전은 의료 관리와 관련된 불필요한 위험을 허용 가능한 최소 수준으로 감소시키는 것으로 정의되기 때문에[3] 병원 내 화재를 관리하는 것은 환자안전 성과를 관리하는 데 중요한 문제가 된다. 세계보건기구에서는 병원이 위기·응급·재난 상황에 대비 하고 안전한 병원이 될 수 있도록 구조적, 비구조적, 기능적 특성을 모두 고려한 이니셔티브와 구체적인 병원 사정 지표를 제시하였다[4,5]. 특히 화재로 인한 위기상황과 관련하여 대피계획을 포함한 화재 안전 프로그램에 대한 규정 및 절차를 갖출 것과, 전 의료종사자가 해당 프로그램을 훈련 받을 것을 권고하고 있다. 또한, 기능적 요소로서 인적자원의 중요성을 강조하고 있으며, 각 기관에서 맞닥뜨릴 만한 원내 위기·응급상황과 재난 상황을 대비하여 조직 차원에서 기획 및 대응팀을 꾸려 연 1~2회의 소방훈련과 시뮬레이션 연습을 실행할 것을 권고하고 있다. 인적자원을 대상으로 한 교육이 지식, 기술, 태도 등 다양한 측면의 역량을 향상시키는 것으로 보고되므로[6] 세계보건기구에서 제시하는 전략은 유효해 보인다.

그러나 국제적 이니셔티브에도 불구하고 여전히 병원내 화재 대응 관련 매뉴얼이 부재하거나, 화재 관리 교육이 부족한 것으로[7,8] 보고되고 있다. 국내의 경우, 「화재예방, 소방시설 설치·유지 및 안전관리에 관한 법률」 제22조제1항, 동 법률 「시행규칙」 제15조제1항에 근거하여 소방훈련 및 소방안전관리교육이 연 1회 필수교육으로 진행되며 병원급 의료기관에서 훈련 시 참고할 수 있는 매뉴얼이 배포되고 있으나[2] 실제 화재 현장에서의 대응은 매뉴얼과 격차를 보이며 화재 관리를 위한 교육에 있어 더 많은 개선점이 필요함을 시사한다[9]. 이에, 이 연구에서는 병원에서 발생하는 화재 대응 교육관련 연구의 동향, 교육의 형태, 교육의 결과를 파악하기 위한 주제범위 문헌고찰을 수행함으로써, 화재안전과 환자안전을 위한 교육을 기획하고 수행하는 부서 및 개인이 조직에 가장 적합한 교육전략을 선택할 수 있도록 하여, 보다 양질의 교육을 제공하고 궁극적으로 화재 대응 결과를 높이는데 기여하고자 하였다.

이 연구는 병원 의료종사자 대상 병원 내 화재 대응 교육의 지형을 파악하기 위한 주제범위 문헌고찰 연구이다. 체계적 문헌고찰이 임상적 의미와 효과성을 밝히는 것에 더욱 중점을 두는 것과 달리, 주제범위 문헌고찰은 특정 개념의 정의를 명확히 하고, 그 특성을 파악하며, 특정 분야에서의 지식 격차를 파악하여 실무에 도움을 줄 수 있는 유용한 근거 제공을 위해 수행된다[10]. 이 연구는, Arksey와 O'Malley의 프레임워크[11]에 따라 1) 연구 질문 확인, 2) 관련 문헌 확인, 3) 문헌 선정, 4) 자료 도표 작성, 5) 결과 수합, 요약, 보고 단계로 수행되었다. 해당 프레임워크는 주제범위 문헌고찰 방법론 최초의 틀로 핵심내용을 모두 다루고 있어[12] 주제범위 문헌고찰 연구의 가이드로 사용된다[13,14].

이 연구의 연구질문은 “의료종사자 대상 병원 내 화재 대응 교육 연구 동향은 어떠한가?”, “교육의 형태는 어떠한가?”, “교육의 주요 결과는 무엇인가?”이다.

최종 검색일인 2022년 8월 24일까지 한국어 혹은 영어로 출판되고 동료 평가된 문헌이 연구의 대상이다. 총 5개의 전자데이터베이스(학술연구정보서비스, PubMed, Cumulative index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature, Web of Science, EMBASE)를 이용하여 검색하였고, ‘Hospital (병원)’, ‘Education (교육, 훈련)’, ‘Fire (화재)’ 3가지 범주를 가지고 PubMed의 의학주제표목 (Medical Subject Headings, MeSH)의 Entry term을 활용하여 검색어 결정한 뒤 ‘AND’, ‘OR’의 연산자 조합하여 검색식을 구성하였으며 검색식은 연구자 소속 의학도서관 사서에 의하여 검토되었다[Appendix 1].

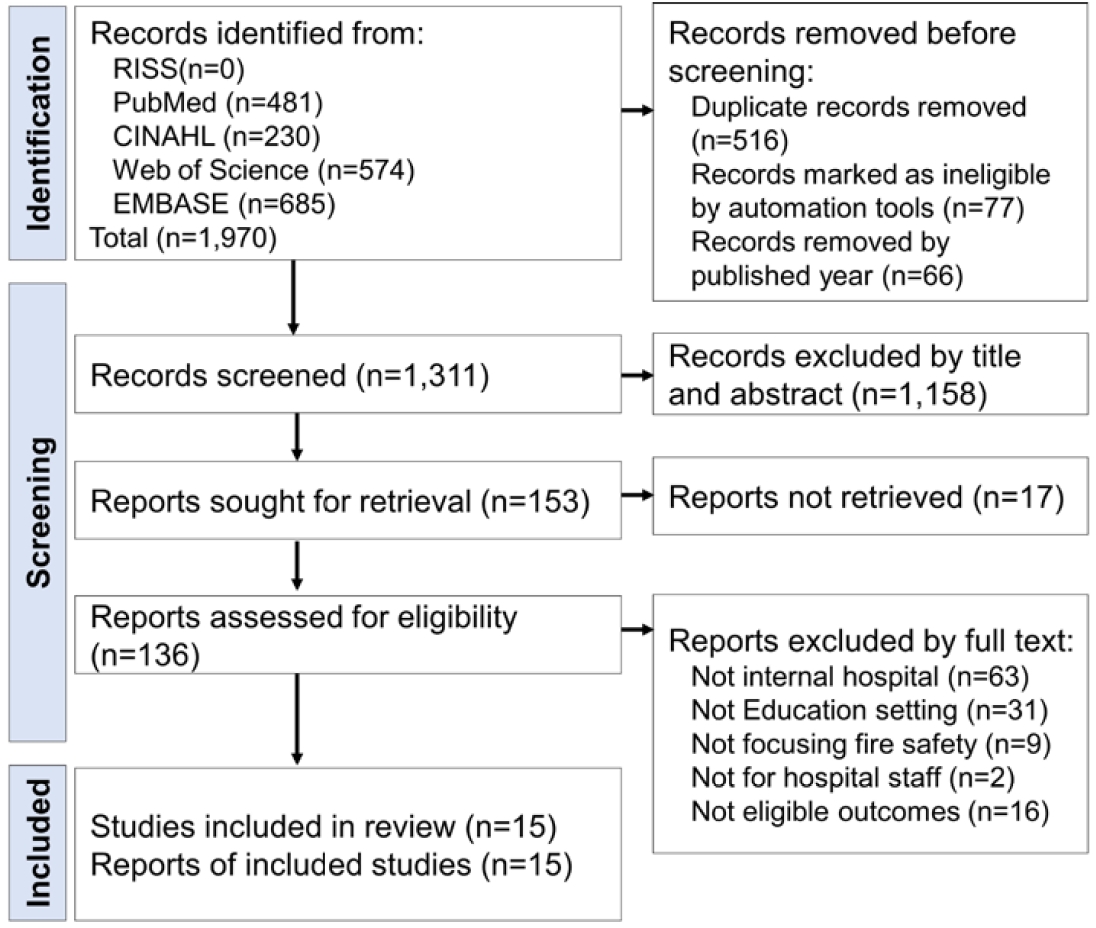

검색된 총 1,970개의 문헌은 서지관리도구(EndNote X9)를 통해 검토 및 분류되었다. 문헌 검토는 Moher와 그의 동료들[15]이 제안한 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)에 따라 수행되었다(Figure 1). 문헌 선정 기준은 1) 병원 의료종사자 대상 병원 내 화재발생 교육을 포함한 문헌, 2) 교육의 성과지표를 보고한 문헌, 3) 1991년 이후에 출판된 문헌이었다. 제외 기준은 1) 실제 화재의 사례보고 등 교육의 효과를 평가하지 않은 문헌, 2) 원문 접근이 불가한 문헌이었다. 문헌선정의 전 과정은 독립된 2인의 연구자를 통해서 진행되었으며, 의견이 일치하지 않은 경우 연구자 회의를 통해 의견을 수렴하였다.

중복으로 검색된 문헌 516건과, 서지관리도구를 통해 국문, 영문이 아닌 것으로 확인된 문헌 77건, 1991년 이전 출판 문헌 66건이 우선 제외되었다. 이후, 제목과 초록 검토과정에서 1,158개의 문헌이 추가로 제외되었고, 원문 접근이 불가능한 17개의 문헌이 제외되었다. 남은 136개 문헌의 전문 확인 과정에서 121개의 문헌이 제외되었으며, 최종적으로 15편의 문헌이 선정되었다[Appendix 2].

이 연구에 최종적으로 포함된 총 15편 문헌의 일반적 특성은 Table 1과 같다. 문헌의 시기별 출판 논문의 편수를 살펴보았을 때, 1991년부터 2004년까지 3편, 2005년부터 2015년까지 3편 2016년부터 2022년까지 9편이 출판되었다. 연구 설계를 보았을 때 12편이 준실험설계[A1-6,A9-10,A12-15]였고 3편이 순수실험설계[A7-8,A11]이었다. 교육이 수행된 국가는 미국이 11편[A1-3,A5-6,A9-13,A15], 벨기에가 2편[A7,A14], 중국이 1편[A8]이었고, 1편[A4]에서는 언급되지 않았다. 교육이 수행된 환경(부서 및 병원)이 언급된 문헌은 7편[A2-3,A6-8, A12,A14]이었고 12개의 수술방 규모[A2]부터 1,000병상 이상의 병원규모[A7]까지 다양했다. 보고된 교육 참여자 수는 11명[A1]에서 180[A15]명까지 다양했지만, 그 수를 보고하지 않았거나 명확하지 제시하지 않은 문헌이 4편[A2-3,A5-6]이었다. 교육 참여자의 직종은 2편[A1,A6]에서는 명확히 기술하지 않았고, 2편[A4,A9]에서는 의사 단일직종이었으며, 이 외의 문헌에서는 다학제, 전문직간 교육이 보고되었다.

문헌에서 보고한 교육의 특성은 Table 2와 같다. 교육은 병원 내 위원회나 팀이 꾸려져 수행된 경우가 4편[A2-3,A6,A15]이었고 그 외에는, 연구자 1인의 주관 하에 수행되었다.

13편의 연구에서 시뮬레이션 방법을 사용하였고[A1-3,A5-7,A9-15], 그 중 실제 병원 현장(In-Situ)에서 수행한 시뮬레이션 8편[A1-3, A5-6, A10-12], 가상현실(Virtual Reality)시뮬레이션 5편[A7,A9,A13-15] 있었다. 이중, 5편의 연구에서는 시뮬레이션 방법에 더불어 강의[A1,A2,A9,A11], 도상훈련[A6] 방법도 사용하였다. 시뮬레이션 방법을 사용하지 않은 연구는 2편으로 시청각자료를 활용한 강의나[A4], 웹 기반 비디오 강의[A8]를 사용하였다. 교육의 빈도는 한 편의 연구[A10]에선 명확하지 않았고, 10편의 연구에서는 1회 제공[A1-6,A8,A11-12,A14], 4편에서는 2회 이상의 교육이[A7,A9,A13,A15] 제공되었다. 교육이 다회 제공 된 경우 모두 가상현실 시뮬레이션 방법을 사용하였다. 교육 소요시간을 명확히 보고하지 않은 8편의 연구[A1-2,A4,A6,A10-11,A13-14]를 제외하고는, 1회당 14분[A8]부터 90분[A12]까지 다양했다.

교육내용을 살펴보면 시뮬레이션 방법을 활용한 경우, 화재 시 행동요령인 Rescue, Alert, Contain, Extinguish/Evacuation (RACE)의 전체 혹은 일부를 다루었다[A1-3,A5-7,A9-15]. 일개 부서 범위 이상의 대응을 요구하는 시나리오를 다룬 경우는 한 개의 연구[A6]에서 확인되었는데 개인의 초동대응을 포함하여 영아 환자의 전원 결정까지를 다루었다. 시뮬레이션 교육을 하지 않은 경우에는 화재 및 화재 대응의 개요를 다루었다[A4,A8].

문헌에서 보고한 교육 결과의 특성은 표2와 같다. 교육 결과는 Kirkpatrick의 4가지 평가 모델에 기반하여 확인되었다. 총 15편의 문헌중, 1단계 반응(reaction, 학습자의 경험)을 평가한 논문은 6편, 2단계 학습(learning, 교육환경에서의 성과)을 평가한 문헌은 15편, 3단계 행동(behavior, 현업에서의 성과)을 평가한 문헌은 2편 있었다. 4단계 결과(result, 환자 결과)를 평가한 문헌은 없었다. 1단계 반응 평가는 참여자의 만족감[A2,A11], 현실성[A12,A15], 유용성[A13,A15] 등으로 보고되었고, 2단계 학습 평가는 화재 대응 전반에 대한 이해, 지식[A1,A4,A7-9,A14] 및 수행[A2-3,A9-13,A15] 자신감/자기효능감[A2,A11,A14-15] 화재대응완료시간[A6-7,A10-11] 등으로 보고되었으며, 3단계 행동 평가는 지식 보유[A11,A14] 등으로 보고되었다.

평가 유형을 살펴보았을 때, 시뮬레이션 후 디브리핑을 통해 정성적 평가만 이루어진 두 편의 문헌[A1-2] 외에는 모두 정량적 평가가 이루어졌다. 일부 문헌에서 팀워크 커뮤니케이션 평가를 위해 TeamSTEPPS를[A5], 동기 측정을 위해 Instructional Materials Motivation Survey[ A7], Instrinsic motivation inventory[A14]를, 자기효능감 측정을 위해 Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire[A14]를 사용하였다. 이 외 문헌에서는 연구자가 개발한 평가지를 활용하거나 특정 과업 달성까지의 시간을 측정하여 교육의 효과를 평가하였다.

교육의 주요 결과를 살펴보면 반응 평가 결과, 교육에 대한 평가는 긍정적이었다[A2-3,A11-13,A15]. 학습 평가 결과, 교육 시 화재 대응이 잘 수행되었으나[A1-3,A9-13,A15], 교육방법과 교보재에 따라 수행정도가 달랐다. 교육 시 화재 대응에 대한 전반적 이해[A1,A4] 및 지식이 향상되었지만[A7-9,A14] 향상 정도의 차이는 교육방법에 따라 불일치한 보고가 확인되었다. 교육 후 참여자들의 화재 대응에 대한 자신감 및 자기효능감[A11,A14-15], 팀워크 및 팀워크 커뮤니케이션에 대한 이해[A5,A12], 동기가 향상되었다[A7,A14]. 화재대응완료시간은 기술적으로 실제 교육 시 소요된 화재대응 시간을 측정하여 보고한 경우가 있었고, 대조군과의 비교를 통해 소요시간을 단축시켰는가를 확인한 경우가 있었는데, 비교연구의 경우 교육 방법에 따른 대응완료시간의 차이는 불일치한 결과를 보고했다. 행동 평가 결과, 한 개의 문헌에서 효율적인 화재 예방을 위하여 부서 내 지침을 변경하였음을 보고하였고[A4], 다른 문헌에서는 교육 현장을 벗어나 현업부서에서도 지식 및 자기효능감이 보유되는 것[A14]로 보고되었다.

이 연구는 병원 의료종사자의 병원 내 화재 대응 교육 관련 연구의 동향, 교육 형태, 교육 결과를 파악하기 위해 수행되었다. 먼저, 본 주제범위 문헌고찰에 포함된 문헌을 분석한 결과, United Nations 세계 재난 감소 회의에서 채택된2005년 효고행동강령[19]과 2015년 센다이 프레임워크[20]를 기점으로 문헌의 수가 증가하는 것을 확인할 수 있다. 두 개의 이니셔티브는, 중추적인 기반시설로서 병원이 재난으로부터 안전할 수 있도록 구조적, 비구조적 투자를 강화할 것과 재난 시 탄력성있는(resilient) 운영이 가능하도록 대응책을 마련할 것을 강조하였다. 증가한 문헌의 수는 이러한 글로벌 이니셔티브에 대한 이해와 화재 위기에 대한 관심이 늘어나고 있는 범국가적인 맥락을 반영한다고 생각한다. 그러나 해당 주제의 중요도나 관심도에 비해 진행된 연구의 수가 많지 않다. 이는 병원의 규모 등에 따라 권고되는 구체적인 교육 기준 및 형태가 존재하지 않기 때문으로 생각되는데, 검토된 문헌들에서 교육이 수행된 병원의 규모, 교육생의 규모가 문헌마다 달랐음이 이를 뒷받침한다. 국내의 경우 역시 의료기관 의료종사자 소방안전 교육에 대한 내용은 의료기관평가인증에 포함되어 있으나, 구체적인 교육 기준이나 형태는 별도로 제시되고 있지 않다.

이 문헌고찰에 포함된 문헌의 대부분에서는 준실험설계 연구방법을 사용하였다. 이는, 임상 현장 교육의 특성 상, 실제 병원의 운영과 의료종사자 업무에 차질을 빚지 않는 선에서 최대한 많은 직원에게 화재 대응 교육을 전달하기 위함이라고 판단된다. 교육 방법과 관련하여서는 시청각 교육, 가상현실 시뮬레이션 교육 등 현실적 장애를 극복할 수 있는 다양한 교육들이 시도되고 있으나, 여러 장점에도 불구하고 교육효과에 대해서는 아직 과학적 근거가 불충분하므로[21] 더 많은 연구가 필요할 것으로 생각된다.

병원 화재 관련 국제 가이드라인은 예측할 수 없는 화재 상황에서 환자의 안전을 보장하기 위해 시설 규정뿐만 아니라 의료종사자들이 화재 안전에 대한 지식과 핵심원칙을 알아야 한다고 강조한다[22]. 본 주제범위 문헌고찰에 포함된 모든 문헌에서는 화재 대응 교육의 내용으로 의료기관 화재의 개요 및 널리 알려진 화재 시 행동요령인 RACE의 전체 혹은 일부 내용을 다루었다. 화재 상황은 희소하고 구현이 쉽지 않기에 행동요령을 체화하는 것이 어렵다. 이 문헌고찰에 포함된 대다수의 문헌에서는 시뮬레이션 교육 방법을 사용하였는데, 아마도 이러한 제한점을 극복하기 위한 것으로 판단한다. 시뮬레이션 교육은 재난 현장을 구현하고 그 속에서 학습효과를 향상시키는 데 효과적인 것으로 알려져 있다[23,24]. 특히 검토된 문헌 중 가상 현실 시뮬레이션 교육을 제공한 5편의 연구 중 4편의 연구[A7,A9,A13,A15]는 높은 재현성. 짧은 소요시간, 다회 교육 제공 가능 등의 장점들을 보였다.

검토된 총 15개의 문헌 중 10개의 문헌[A1-3,A5,A9-13,A15]은 수술실이라는 특정 환경에서의 화재 대응 교육을 다루었다. 해당 문헌에서 사용한 시나리오는 수술실 내 초기 화재 대응 방법에 한정되었으며 수술실에서 환자 대피 이후 환자의 거취와 수술실 부서 전체의 대피를 고려한 내용이 포함되지는 않았다. 수술실뿐만 아니라 중환자실과 같은 특수부서에는 산소를 포함한 의료장비에 대한 의존도가 높고, 대피 시 이동에 취약한 환자들이 많기 때문에 의료종사자들이 기본적인 화재대응방법을 알고 있는 것만으로는 실제 화재 상황에서 의사결정에 어려움을 겪을 수 있다. 선행 문헌에서도 실제 초기 화재 진압 실패 후 대피에 대한 준비는 잘 되어 있지 않은 것으로 보고되고 있다[25,26]. 하지만 응급 대피 시 필요사항에 대한 병원의 철저한 사전계획이 화재 대피 시 가장 큰 영향을 미치는 것으로 보고되고 있어[27] 화재 대응 교육에는 산소차단밸브. 대피경로, 대피보조장치, 집결지 등의 내용을 포함하는 치료연속성을 유지하기 위한 구체적인 계획을 포함할 필요가 있음을 보여준다[28]. 이러한 교육이 가능하기 위해서는 계획 단계부터 리더십의 지원을 받으며, 비의료인 및 의료인을 포괄한 다직종, 다부서가 함께 교육을 준비하는 것이 필요할 것이다. 이 연구에서 검토된 15개 문헌 중 11개의 연구[A1,A4-5,7-14]는 연구자 개인에 의하여 주도되었으나, 세계보건기구 서태평양지역사무소[4]는 환자안전 친화적인 병원을 위하여 비상사태와 재난에 적절하게 대응하기 위한 비상계획위원회를 조직하고 그들을 주최로 교육을 진행할 것을 강조하였다. 또한 범미보건기구가 병원 화재 관리에 대하여 안내한 보고서[20]에 따르면 병원화재의 주 원인은 주방기기, 적재된 쓰레기, 전기배선 또는 조명 등으로 특정 부서에 국한된 원인이 아니므로 화재 대응 교육 시 병동이나 외래, 비진료부서를 포괄해서 진행하는 것이 필요하다. 다부서 교육은 현실적인 시간 및 자원의 제약이 있으나, 소방 및 재난 연구에서 최근 사용되고 있는 가상현실을 통한 교육방법[29]을 통해 이러한 장애를 극복할 수 있을 것이다. 다만, 이 연구에서 검토된 가상현실 시뮬레이션을 사용한 교육[A7, A9, A13-15]은 시나리오 상 초동대응을 주로 다루고 있었기에, 추후 다부서, 다직종 협력, 전원까지 교육할 수 있는 시나리오 내용을 구성할 필요가 있다.

Kirkpatrick의 4단계 평가 모델에 기반하여 검토된 문헌의 교육 결과의 특성을 확인해 본 결과, 화재 대응 교육은 대상자의 만족도, 성취감, 현실성, 직무연관성에서 긍정적인 반응을 이끌어냈고(1단계), 지식, 동기, 하드 스킬 및 소프트 스킬을 향상시켰으며(2단계), 지식 및 자기효능감의 현업 이전을 가능하게(3단계) 하였다. 화재 대응 교육의 궁극적 목적은 실제 화재 상황에서 환자 건강 결과를 향상시키는 것이므로 3단계 행동 및 4단계 환자 건강 결과는 중요하게 측정되어야 하는 결과변수이다. 3단계 행동 평가를 진행한 연구는 2편[A11,A14]있었으나 지식 보유 정도에 대한 분석 방법 차이로 인해 일관된 결과를 생성했다고 보기 어려웠으며, 4단계 환자 건강 결과 평가를 진행한 연구는 없었다. 이는 지표 설정의 한계에 따른 것으로 추정한다. 이러한 한계를 극복하기 위해 시나리오 내 환자의 생리 변화 구현 및 건강 결과 설정이 가능한 하이테크 시뮬레이터나 가상현실을 교육 방법을 사용할 수 있을 것이다. 또한, 환자 건강 결과 지표를 포함하는 화재 대응 교육 설계를 함으로서, 해당 교육이 위기상황에서 환자 안전 성과를 높이는지 확인하는 추후 연구가 필요할 것이다.

이 연구는 영어와 한국어로 출판된 동료 평가를 받은 문헌만 포함하였기에, 기타 다른 언어로 출판된 문헌이나 회색문헌들은 포함하지 못했다는 제한점이 있다. 또한, 환자 안전의 측면에 초점을 두고 검색을 하였기에, 광범위한 데이터베이스 검색을 수행했음에도 불구하고 방재 시설 관리 등 화재 관리의 일부를 다루는 타 학문분야의 연구는 포함되지 않았을 가능성이 있다.

환자 안전을 위하여 병원 의료종사자들이 병원 내 화재 대응에 대한 충분한 지식 및 수행능력을 갖추는 것은 중요하다. 본 주제범위 문헌고찰 연구는 병원 의료종사자를 대상으로 한 병원 내 화재 대응 교육의 동향, 특성 및 결과를 파악하기 위해 수행되었다. 이 연구의 결과, 화재 대응 교육은 의료종사자들의 업무편의성을 우선적으로 고려하여 다수의 교육 대상자들이 편한 시간과 장소에서 참여할 수 있도록 진행되었다. 또한 비교적 짧은 시간에 다회 교육이 가능한 가상현실을 활용한 교육을 도입하여 시간효율적인 형태로 발전하였다. 대부분의 교육에서는 화재 시 행동요령인 RACE와 관련된 내용을 다루었다. 교육 대상자는 교육이 긍정적인 경험이었다고 보고 하였으며, 교육의 효과는 화재 대응 지식부터 빠른 화재 대응 완료까지 다양하게 성취되었다.

화재 대응 교육은 수월성과 효과성을 향상하여 궁극적으로 환자의 안전을 보장하는 결과로 이어져야 한다. 이를 위해 교육 시나리오 설계 시 특수한 요구가 있는 환자군이 존재하는 병원의 특성을 생각하여 초동 대응뿐 아니라 이후 대피 단계까지 고려한 시나리오를 개발할 것을 제언한다. 또한 교육 평가 설계 시 환자의 건강 결과 측면의 효과를 포함할 것을 제언한다. 마지막으로, 복잡한 실제 화재 상황을 고려한 교육이 가능하도록 기관 차원의 이니셔티브에 기반하여 다직종, 다부서의 의료종사자가 함께 교육을 개발하고 교육에 참여하여야 할 것이다.

Table 1.

General characteristics of study.

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes of program.

REFERENCES

1. Campbell R. Structure fires in health care facilities. MA, USA: National Fire Protection Association; 2017.

2. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Fire safety manual of medical institutions. Sejong Special Self-Governing City, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2022.

3. Runciman W, Hibbert P, Thomson R, Van Der Schaaf T, Sherman H, Lewalle P. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: key concepts and terms. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2009;21(1):18-26 https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzn05. PMID: 19147597

4. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Safe hospitals in emergencies and disasters: structural, non-structural and functional indicators. Manila, Philippines: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2010.

5. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Patient safety assessment manual, 3rd ed. Cairo, Egypt: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2020.

6. Loke AY, Guo C, Molassiotis A. Development of disaster nursing education and training programs in the past 20 years(2000-2019): A systematic review. Nurse Education Today. 2021;99:104809 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104809. PMID: 33611142

7. Greenidge C, Cawich SO, Burt R. Francis T. Major Hospital Fire in Saint Lucia. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2021;36(6):797-802 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000947. PMID: 34556194

8. Jardaly A, Arguello A, Ponce BA, Leitch K, McGwin G, Gilbert SR. Catching Fire: Are Operating Room Fires a Concern in Orthopedics? Journal of Patient Safety;. 2022;18(3):225-229 http://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000896px.

9. Choi D, Lim J, Cha MI, Choi C, Woo S, Jeong S, et al. Analysis of Disaster Medical Response: The Sejong Hospital Fire. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. Cambridge University Press;. 2022;37(2):284-289 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X22000334.

10. Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018;19;18(1):143 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. PMID: 19

11. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19-32 https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

12. Seo HJ. The Scoping Review Approach to Synthesize Nursing Research Evidence. Korean Society of Adult Nursing. Korean Journal of Adult Nurssing. 2020;32(5):433-439 https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2020.32.5.433.

13. Noh YG, Lee OS. Ethical Climate of Nurses in Korea: A Scoping Review. The Journal of Korean Nursing Administration Academic Society. 2022;28(5):487-498 https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2022.28.5.487.

14. Drake SA, McDaniel M, Pepper C. A scoping review of nursing education for firearm safety. Nurse Education Today. 2023;121:105713 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105713. PMID: 36657319

15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. PMID: 19621072

16. Brottman MR, Char DM, Hattori RA, Heeb R, Taff SD. Toward Cultural Competency in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Diversity and Inclusion Education Literature. Academic Medicine. 2020;95(5):803-13 http://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002995. PMID: 31567169

17. Geng C, Luo Y, Pei X, Chen X. Simulation in disaster nursing education: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today. 2021;107:105119 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105119. PMID: 34560394

18. Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE guide no. 67. Medical Teacher. 2012;34(5):e288-99 https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.668637. PMID: 22515309

19. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction. Hyogo framework for action 2005-2015: building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction; 2007.

20. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; 2015.

21. Brown N, Margus C, Hart A, Sarin R, Hertelendy A, Ciottone G. Virtual Reality Training in Disaster Medicine: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Simulation in Healthcare. 2022. http://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000675.

22. Pan American Health Organization. Hospitals don't burn! Hospital fire prevention and evacuation. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2014.

23. Warren JN, Luctkar-Flude M, Godfrey C, Lukewich J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation-based education on satisfaction and learning outcomes in nurse practitioner programs. Nurse Education Today. 2016;46:99-108 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.023. PMID: 27621199

24. Jung Y. Virtual Reality Simulation for Disaster Preparedness Training in Hospitals: Integrated Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2022;24(1):e30600. http://doi.org/10.2196/30600. PMID: 35089144

25. Löfqvist E, Oskarsson Å, Brändström H, Vuorio A, Haney M. Evacuation Preparedness in the Event of Fire in Intensive Care Units in Sweden: More is Needed. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2017;32(3):317-320 https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X17000152. PMID: 28279230

26. Murphy GR, Foot C. ICU fire evacuation preparedness in London: a cross-sectional study. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2011;106(5):695-8 https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer033. PMID: 21414979

27. Sahebi A, Jahangiri K, Alibabaei A, Khorasani-Zavareh D. Factors Influencing Hospital Emergency Evacuation during Fire: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2021;12:147 https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_653_20. PMID: 34912523

28. Kelly FE, Bailey CR, Aldridge P, Brennan PA, Hardy RP, Henrys P, et al. Fire safety and emergency evacuation guidelines for intensive care units and operating theatres: for use in the event of fire, flood, power cut, oxygen supply failure, noxious gas, structural collapse or other critical incidents: Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists and the Intensive Care Society. Anaesthesia. 2021;76(10):1377-91 https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15511. PMID: 33984872

29. Li NF, Xiao Z. A Fire Drill Training System Based on VR and Kinect Somatosensory Technologies. International Journal of Online and Biomedical Engineering. 2018;14(4):https://doi.org/10.3991/ijoe.v14i04.8398.

APPENDICES

Appendix 1.

Database Search Strategy

Appendix 2.

Studies Included in Scoping Review

A1. Halstead MA. Fire drill in the operating room. Role playing as a learning tool. AORN Journal. 1993;58(4):697-706. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-2092(07)65267-3

A2. Flowers J. Code red in the OR-implementing an OR fire drill. AORN Journal. 2004;79(4):797-805. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60820-x

A3. Salmon L. Fire in the OR—Prevention and preparedness. AORN Journal. 2004;80(1):41-54.

A4. Lypson ML, Stephens S, Colletti L. Preventing surgical fires: who needs to be educated? Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety. 2005;31(9):522-527. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31067-1

A5. Hohenhaus SM, Hohenhaus J, Saunders M, Vandergrift J, Kohler TA, Manikowski ME, et al. Emergency response: lessons learned during a community hospital's in situ fire simulation. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2008;34(4):352-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2008.04.025

A6. Femino M, Young S, Smith VC. Hospital-based emergency preparedness: evacuation of the neonatal intensive care unit-the smallest and most vulnerable population. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(1):107-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e31827b8bc5

A7. All, A, Plovie, B, Castellar, EPN, Van Looy J. Pre-test influences on the effectiveness of digital-game based learning: A case study of a fire safety game. Computers & Education. 2017;114, 24-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.018

A8. Lee PH, Fu B, Cai W, Chen J, Yuan Z, Zhang L, et al. The effectiveness of an on-line training program for improving knowledge of fire prevention and evacuation of healthcare workers: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0199747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199747

A9. Sankaranarayanan G, Wooley L, Hogg D, Dorozhkin D, Olasky J, Chauhan S, et al. Immersive virtual reality-based training improves response in a simulated operating room fire scenario. Surgical Endoscopy. 2018 Aug;32(8):3439-3449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6063-x

A10. Acar YA, Mehta N, Rich MA, Yilmaz BK, Careskey M, Generoso J, et al. Using Standardized Checklists Increase the Completion Rate of Critical Actions in an Evacuation from the Operating Room: A Randomized Controlled Simulation Study. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2019;34(4):393-400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X19004576

A11. Kishiki T, Su B, Johnson B, Lapin B, Kuchta K, Sherman L, et al. Simulation training results in improvement of the management of operating room fires-A single-blinded randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Surgery. 2019;218(2):237-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.02.035

A12. Mai CL, Wongsirimeteekul P, Petrusa E, Minehart R, Hemingway M, Pian-Smith M, et al. Prevention and Management of Operating Room Fire: An Interprofessional Operating Room Team Simulation Case. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;24;16:10871. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10871

A13. Qi D, Ryason A, Milef N, Alfred S, Abu-Nuwar MR, Kappus M, et al. Virtual reality operating room with AI guidance: design and validation of a fire scenario. Surgical Endoscopy. 2021;35(2):779-786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-07447-1

A14. Rahouti A, Lovreglio R, Datoussaïd S, Descamps T. Prototyping and validating a non-immersive virtual reality serious

game for healthcare fire safety training. Fire technology. 2021;1-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10694-021-01098-x

A15. Truong H, Qi D, Ryason A, Sullivan AM, Cudmore J, Alfred S, Jones SB, Parra JM, De S, Jones DB. Does your team know how to respond safely to an operating room fire? Outcomes of a virtual reality, AI-enhanced simulation training. Surgical Endoscopy. 2022;36(5):3059-3067. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08602-y

Appendix 3.

Summary of General Characteristics of studies

| Article | 1st Author (year) | Study Design | Setting (Country) | Samples Total (EG1)/CG2)) | Participant’s Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Halstead (1993) | Post test only | N/R3) (USA) | 11-12 people in each OR4) | Unclear |

| A2 | Flower (2004) | Post test only | 12 OR (USA) | N/R | Registered nurse, Licensed practical nurse, surgical technologist, and nursing assistant |

| A3 | Salmon (2004) | Post test only | 300 beds (USA) | N/R | OR and anesthesia staff |

| 28 OR | |||||

| A4 | Lypson (2005) | Post test only | N/R (N/R) | Training1: 152 | Training1: Intern, resident |

| Training2: N/R | Training2: anesthesia and surgical faculty | ||||

| A5 | Hohenhaus (2008) | Post test only | N/R (USA) | N/R | Unclear |

| A6 | Femino (2013) | Post test only | 600 beds (USA) | Unclear | Neonatologists, advanced practice nurse, clinical nurses, respiratory therapist, unit coordinators, administrative staff |

| 40 NICU5) beds | |||||

| A7 | All (2017) | Solomon four group | 1000+ beds (Belgium) | 133 (65/69) | Doctors, nurses, cleaning personnel, administrative staff, technical staff |

| A8 | Lee (2018) | RCT | 500+ beds (China) | 128 (64/64) | Doctor, nurse, therapist |

| A9 | Sankaranarayana (2018) | Pre-post test | N/R (USA) | 20 (10/10) | General Surgery residents, OBGYN6) residents. |

| A10 | Acar (2019) | RCT | N/R (USA) | 28 (15/13) | 2, 3year anesthesia residents, nurse anesthetists, OR nurses |

| Post test only | |||||

| A11 | Kishiki (2019) | RCT | N/R (USA) | 82 (53/29) | Surgeon, physician assistant, anesthesia OR nurse, surgical tech |

| Retention test | |||||

| A12 | Mai (2020) | Post test only | 999 beds (USA) | 86 | Surgery residents, surgery intern, senior anesthesia resident, junior anesthesia resident(or certified registered nurse anesthetist), OR nurse, surgical technologist |

| A13 | Qi (2021) | Post test only | N/R (USA) | 53 | Attendings, fellows, residents, others |

| A14 | Rahouti (2021) | Pre-post-retention test | 270 beds (Belgium) | 78 (31/47) | Administrative staff, nurses, cleaning personnel, doctors, technical staff |

| A15 | Truong (2022) | Pre-post test | N/R (USA) | 180 | Surgeons, anesthesiologists, registered nurse, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, scrub technicians, medical students, residents, and fellows |

Appendix 4.

Summary of Characteristics and Outcomes of Programs

| Article | 1st Author (year) | Initiative | Module | Contents | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Halstead (1993) | Researcher | Training 1: | Elements of fire | Training 1: |

| Lecture using video | Initiate alerting | Evacuated safely | |||

| Orientation | Evacuate patients safely | Training 2: | |||

| Single trial of in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using SP1) at OR2) | Use fire extinguisher (PASS3)) | Better understanding of fire fighting | |||

| Report sharing | |||||

| Training 2: | |||||

| Lecture | |||||

| Fire Extinguisher demonstration by fire officer at local fire department | |||||

| A2 | Flower (2004) | A fire safety committee | Lecture by unit education manager | Fire policy | Everyone was pleased with fire drill |

| Single trial of in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using SP and fake flame at OR | Avoid smoke inhalation | ||||

| Alarm | Showed good performance based on learned knowledge | ||||

| Critique | Extinguish a fire | ||||

| Evacuate | |||||

| A3 | Salmon (2004) | Planning committee | Single trial of 1hr in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using low-fidelity manikins, SP and fire extinguisher at OR | RACE4) | Feeling of accomplishment |

| Needs for fire drills | |||||

| Good performance of RACE | |||||

| A4 | Lypson (2005) | Researcher | Training 1 | Overview of fire in facility | Training 1: |

| Single trial of audio-visual lecture at separate training station and brochure during intern orientation | Understanding prevent surgical fires | ||||

| Test | Training 2: | ||||

| Training 2 | Policies are reviewed & updated | ||||

| Audio visual lecture with brochure, and continuous displaying posters and signage | |||||

| A5 | Hohenhaus (2008) | Unit member | 1hr program of setup, in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using a low-fidelity manikin at OR, and debriefing | Remove the fuel, oxygen source | Team communication concept was improved |

| Contain and extinguish fire | |||||

| Alarm personnel | Adherence to hospital policy was important | ||||

| Shut off electricity | |||||

| Evacuate a patient | |||||

| A6 | Femino (2013) | Planning team | Table-top exercise rehearsal | Vertical evacuation | Horizontal evacuation took 3min |

| Single trial of in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using simulated infants manikin, communication software (webEOC5)) at multisite in hospital | Transfer to other hospital | Obtaining statewide NICU6) beds took 1.5hrs | |||

| A7 | All (2017) | Researcher | EG7): | EG: | Both groups score better than before education (EG scored better than CG) in knowledge test |

| 4 trials (3 scenarios & 1 random scenario) of digital-game based drill with laptop computer and headphone for 35min | Alarm internally/externally, right position to open the door, extinguish fire, evacuate mobile, wheelchair, immobile patients | ||||

| CG8): | CG: | Both groups score better than before education (EG scored better than CG) in motivation | |||

| 25min a slide-based lecture (3 themes as same as game scenarios). with actual fire extinguisher, a fire blanket and a fire horse | Right steps and procedure in fire | EG took less time than CG | |||

| A8 | Lee (2018) | Researcher | EG: | EG: | Generic Knowledge of fire prevention and evacuation was improved |

| Single trial of 14min web-based video lecture | Basic response to a hospital fire and patient evacuation methods | ||||

| Knowledge test | |||||

| CG: | CG: | ||||

| Single trial of 6min web-based video lecture | Introducing volcanic disaster | ||||

| Knowledge test | |||||

| A9 | Sankaranarayana (2018) | Researcher | EG: | Discontinue of the anesthesia mask | Training 1: |

| Pre-test | Turn off the gas | Knowledge was improved (no difference between EG and CG) | |||

| A 15min in-person lecture based on SAGES9) FUSE10) manual | Removal of the surgical drape | ||||

| 5trials of immersive VR11) simulation drill with HMD12), handheld and trigger switch | Extinguish fire | Training 2: | |||

| Post-knowledge test | EG is better than CG in performance | ||||

| Post-simulation test using high fidelity mannequin at operative skills lab | |||||

| CG: | |||||

| Pre-test | |||||

| A 15min in-person lecture based on SAGES FUSE manual | |||||

| Post-knowledge test | |||||

| Post-simulation test using high fidelity mannequin at operative skills lab | |||||

| A10 | Acar (2019) | Researcher | EG: | Manage hypotensive event for warming up Install Leadership Evacuate one operating patient | EG did more critical actions than CG |

| In-situ scenario-based simulation using high fidelity manikin, evacuation device and checklist at OR | No difference between EG and CG in evacuation time | ||||

| CG: | |||||

| In-situ scenario-based simulation using high fidelity manikin and evacuation device at OR | |||||

| A11 | Kishiki (2019) | Researcher | EG: | Risk Assessment | Both group highly rated the course |

| Single trial of in-situ scenario-based simulation exercise using high fidelity manikin and fog machine at OR | Recognition and Alarm | ||||

| Pre-test | Identifying, controlling and removing fuel and turning off oxygen from patient | EG got more confidence than CG | |||

| Lecture | |||||

| Single trial of In-situ scenario-based simulation post- test at OR | Extinguishing Fire | EG did more critical actions than CG | |||

| Retention-test | Event follow-up | ||||

| CG: | EG took less time to complete critical actions than | ||||

| Pre-test | |||||

| Lecture | CG | ||||

| Single trial of In-situ scenario-based simulation post- test at OR | No difference between EG and CG in Knowledge | ||||

| Retention-test | |||||

| A12 | Mai (2020) | Researcher | OT13) | Identifying situations | Realistic (80.0%) |

| Single trial of 90min in-situ scenario-based simulation Exercise using high-fidelity manikin at OR | Manage OR fire in RACE | Relevance (93.0%) | |||

| Reduce adverse outcomes | Changed their practice (82.0%) | ||||

| Debriefing with recording system | Apply crisis management | Promoted teamwork (80%) | |||

| A13 | Qi (2021) | Researcher | OT | Principle of the fire triangle and FUSE curriculum | Face validity were rated greater (72.7%) |

| Practice | AI guidance was useful (79.3%) | ||||

| 2trials of immersive VR simulation Exercise1 using HMD and hand-held controllers at SAGES annual conference | AI14) guidance improved the performance significantly | ||||

| 1~3 trials of Immersive VR simulation Exercise2 using HMD and hand-held controllers with Virtual Intelligent Preceptor (VIP) at SAGES annual conference | |||||

| Questionnaire | |||||

| A14 | Rahouti (2021) | Researcher | EG: | Principle of the fire reaction fire categories, fire prevention measures, emergency signs, fire detection concepts of announcement, alert, and alarm evacuation procedure | EG showed improvement in Knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy in after test and retention test |

| Pre-test | |||||

| Single trial of non-immersive VR Exercise using personal computer, mouse and keyboard | |||||

| Post-Test | |||||

| Retention-Test | Change of Intrinsic motivation was not significant | ||||

| CG | |||||

| Pre-test | |||||

| Slide based lecture | |||||

| Post-test | |||||

| Retention-test | |||||

| A15 | Truong (2022) | group | OT | Extinguish OR fire within 2 min based on fire triangle and FUSE guideline | Experienced favorably |

| acclimatization time | Respond to confident (45.4%) | ||||

| pre-survey | |||||

| 3 trials of 2min immersive VR simulation exercise using HMD and hand-held controllers | Pass on simulation test EG (54%)>CG (24%) | ||||

| 2 trials of 2min immersive VR simulation exercise using HMD and hand-held controllers with AI guidance | Many trials help to pass | ||||

| post-survey |