A Bundled Educational Solution to Reduce Incorrect Plaster Splints Applied on Patients Discharged from Emergency Department

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Plaster splints are routinely performed in the Emergency Department (ED) and avoidable complications such as skin ulcerations and fracture instability arise mainly due to improper techniques. Despite its frequent use, there is often no formal training on the fundamental principles of plaster splint application for a medical officer rotating through ED. We aim to use Quality Improvement (QI) methodology to reduce number of incorrect plaster splint application to improve overall patient care via a bundled educational solution.

Methods

We initiated a QI program implementing concepts derived from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement models, including Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, to decrease the rate of incorrect plaster splint application. A bundled education solution consisting of three sequential interventions (practical teaching session, online video lecture and quick reference cards) were formulated to specifically target critical factors that had been identified as the cause of incorrect plaster splints in ED.

Results

With the QI intervention, our overall rate of incorrect plaster splints was reduced from 84.1% to 68.6% over a 6-month period.

Conclusion

Following the QI project implementation of the bundled educational solution, there has been a sustained reduction in incorrect plaster splints application. The continuation of the training program also ensures the sustainability of our efforts in ED.

Ⅰ. Introduction

Plaster splints are an integral part of Emergency Department (ED) patient management. They are frequently used as a treatment for traumatic injuries such as fractures, post manipulation and reduction (M&R) for some types of fracture-dislocations, immobilization for severe sprains and other musculoskeletal pathologies [1]. Complications can occur from application of plaster splints to the immobilization process and during removal of plaster splints [2]. These complications include skin injuries, abrasions and ulcerations, compartment syndrome and malreduction [2-7]. The causes of these complications were mainly due to improper technique resulting in avoidable skin complications and fracture instability [2-4,7-8].

Despite its frequent use, there is often no formal training for an emergency physician on the fundamental principles of plaster splints application [3,9]. Plastering skills in the ED by Junior Doctors have been shown to be suboptimal despite having to apply these plaster splints very frequently during the ED rotation [10]. At the ED, plaster splints are often applied by Junior Doctors who are not equipped with adequate knowledge and skills in plastering technique due to the lack of formal training. Follow up visits to the orthopaedic or hand surgery outpatient clinics, often result in feedback pertaining to poor standard and improperly placed plaster splints. Such incorrectly applied splints can potentially result in splint ineffectiveness and undesirable complications.

Therefore, we decided to implement QI concepts derived from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement models, including the PDSA cycles, to perform a QI initiative in one of the largest EDs in Singapore, with the aim to decrease the rate of incorrect plaster splint application.

Ⅱ. Methods

The objective of this QI project is to decrease the rate of incorrect plaster splints applied on patients discharged from SGH DEM (Sigapore Govement Hospital Department Emergency Medical) by 50% in 6 months (October 2020 to April 2021). Based on institutional guidelines, approval for this QI project was obtained from the Chairman of Division of Medicine and exempted from review by the Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB).

Direct feedback was first obtained from the Plaster Room Staff. This confirmed the feedback regarding incorrect plaster splints applications. Our team also realised that the definition of an “incorrect plaster splint” could vary, especially since there were no official guidelines on correct plaster splints. There are several plaster splint methods in use since ancient times to immobilise fractures, therefore the need for standardisation with formal training [11,12].

The Plaster Room staffs are trained and specialized in plaster splint removal and application. They work with plaster splints and casts daily. Using them as the expert reference, our QI team interviewed them to establish the important aspects of a plaster splint. We then decided on six characteristics which would ultimately determine if a plaster splint was done correctly. These six characteristics were protection of pressure points, length, width, thickness, goodness of fit and tightness.

With this information, a data collection system consisting of survey forms (Appendix A) was then created to collect baseline and prospective data [13]. The Plaster Room Staff would fill up a survey form for each patient who had a plaster splint applied in ED, to assess the characteristic of the splint and the presence of any complications. We relied on the expert opinion of the Plaster Room Staff to determine the correctness of the plaster splints based on the six identified characteristics. The filled survey forms were used to calculate the rate of incorrect plaster splints.

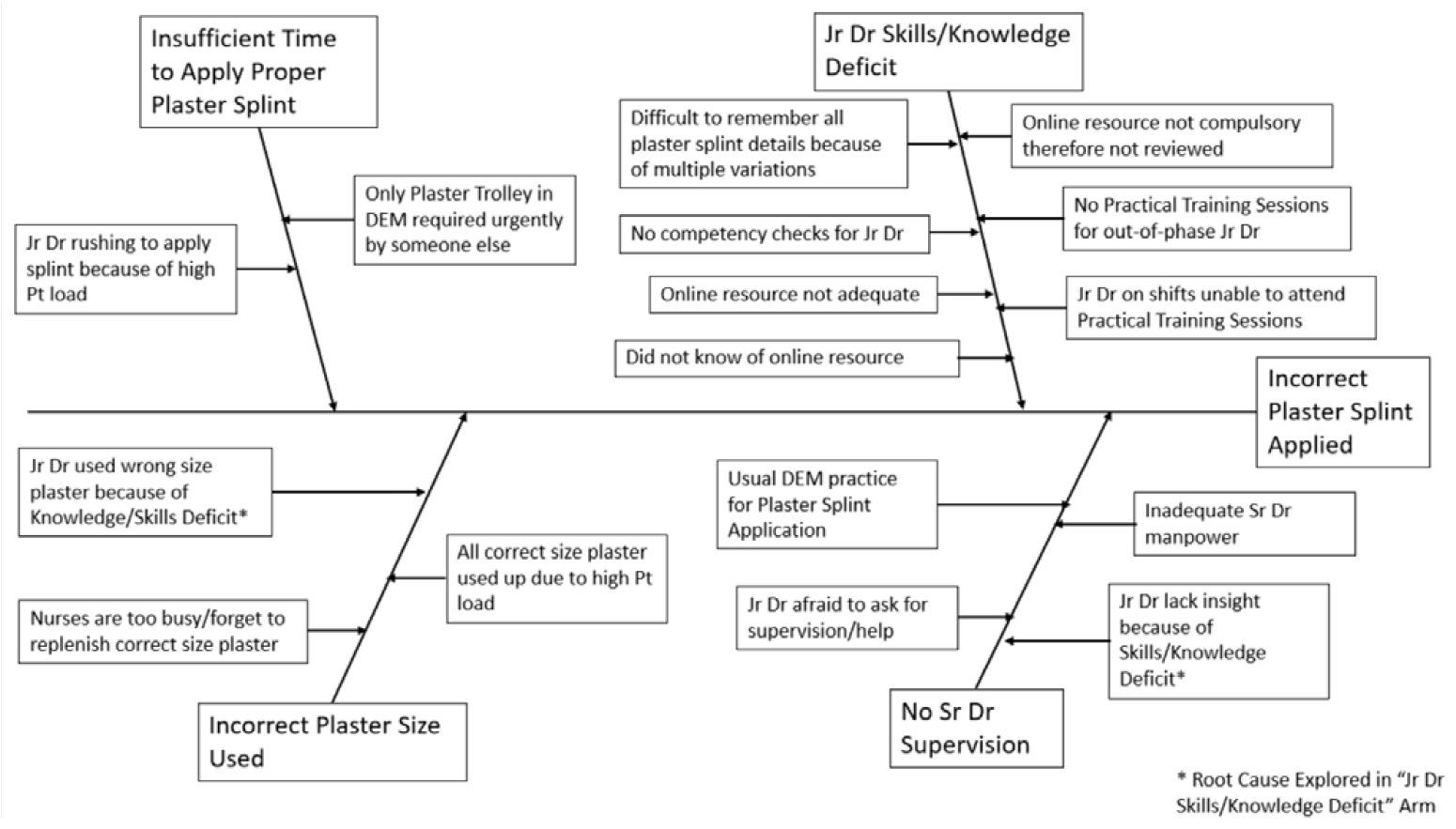

Fishbone Diagram: Cause and Effect Analysis

We use a Fishbone Diagram to perform a cause and effect analysis to identify the root causes for the incorrect plaster splints applied on patients in ED. A total of 14 factors were identified (Figure 1).

This was followed by a voting-based Pareto process to rank the importance of the various factors, from which emerged four critical factors that the team determined could yield the greatest improvement if targeted (Table 1). Applying the 80:20 principle on our Pareto Chart, we identified the “vital few” factors (Figure 2). A bundled education solution was designed to address these identified factors (Causes A-D):

A. Current online resource not adequate

B. Difficult to remember all plaster splint details because of multiple variations

C. Junior Doctors on shifts unable to attend Practical Training Sessions

D. No Practical Training Sessions for out-of-phase Junior Doctors

For the purpose of our QI study, Junior Doctors are defined as doctors of rank below that of Registrar

Interventions

Our bundled education solution (Appendix B) was formulated to specifically target the factors that had been identified from the Pareto process. It comprises of three sequential interventions:

1. Practical Teaching Session,

2. Online Video Lecture and

3. Quick Reference Cards

These interventions were essentially of the same clinical content but delivered via different modes. These interventions were executed over three months within our QI study period.

For our 1st intervention, our team chose to target Cause D (No Practical Training Sessions for outof-phase Junior Doctors) because it addressed both the knowledge and skills deficit of Junior Doctors. In addition, it allows us to test our teaching materials before converting it into other versions. We planned for Junior Doctors Practical Teaching Sessions to help Junior Doctors gain both knowledge and skills in doing proper plaster splints. Given that Practical Teaching Sessions would last approximately 2 hours, the time and effort invested would be minimal given the large impact. This intervention would also target Cause C (Junior Doctors on shifts unable to attend Practical Training Sessions) as well if we continued to hold similar teaching sessions on a regular basis (i.e. every 2 months), allowing Junior Doctors who missed the 1st session to attend the Practical Teaching Session.

We decide to focus on Cause A (Current online resource not adequate) next for our 2nd intervention by creating and uploading new videos/resources. Although this took a significant amount of effort and time, we decided for it because it could also target Cause C (Junior Doctors on shifts unable to attend Practical Training Sessions) too as Junior Doctors would be able to gain knowledge on plaster splints by reviewing these videos/resources in their own free time.

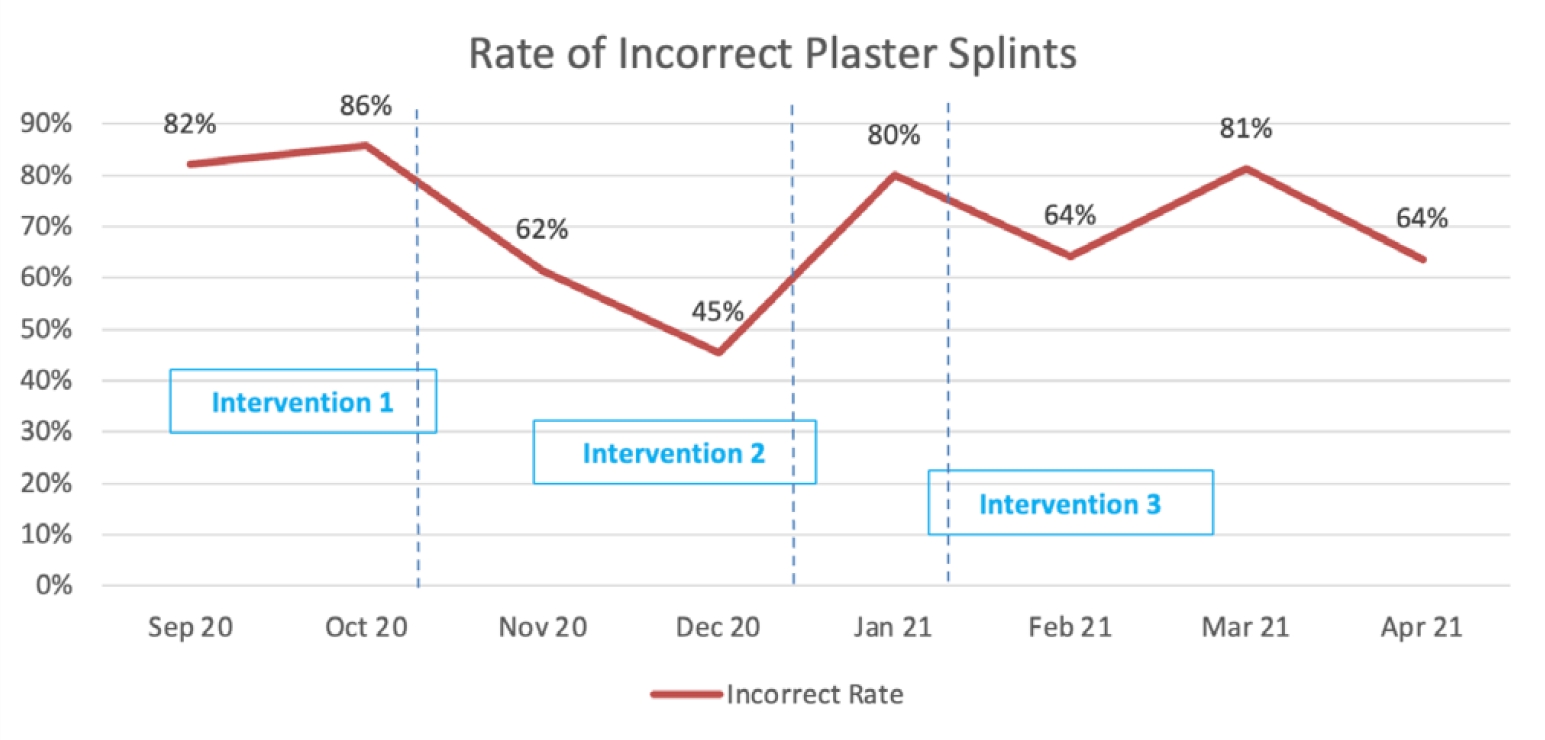

Both the 1st and 2nd interventions targeted Cause B (Difficult to remember all plaster splint details because of multiple variations) too as knowledge is transferred via repetition. However, the impact on Cause B would be very limited. We required a solution which was focused solely on Cause B. Hence, our team created a set of Quick Reference Cards at the Plaster Trolley for Junior Doctors to refer when doing plaster splints. This 3rd intervention helped as an instant reference with specific instructions to all variations of plaster splints, hence it was likely to be the most impactful. However, a lot of time and effort was required for the creation of these cards. As such, we did it later in the project. The run chart of incorrect plaster splints versus our interventions is presented in Figure 3.

Ⅲ. Results

Following the QI project implementation, a total of 53 Junior Doctors underwent our education intervention. The overall rate of incorrect plaster splints was reduced from 84.1% to 68.6% (Table 2) over a 6-month period.

Ⅳ. Discussions

The primary goal of this QI intervention was to improve patient care by reducing the numbers of incorrect plaster splint applications. Our findings of an overall incorrect plaster splints rate of 84.1% are comparable with prior studies [5,6] showing high rates of technical errors of plaster splint placement. There were studies demonstrating the benefits of formal training, teaching videos and simulation-based education in reducing plaster splint complications [14-16].

Hence, we implemented a formalized training program with an educational bundle for all Junior Doctors on rotation posting to ED. The educational bundle consisted of practical teaching sessions, online video lectures and quick reference cards. The content of the practical sessions, online video lectures were based off the quick reference cards for consistency.

In the quick reference cards (Appendix B), we emphasised on the 5 important yet fundamental steps on plaster splint application to reduce splint-related complications – namely 1) Protect the skin, 2) Measure and layer the plaster bandages, 3) Wet the plaster bandages, 4) Position plaster splint on patient’s limb, 5) Mould the plaster and bandage the limb. The reference guide has a comprehensive list of specific upper and lower limb fractures, the position of the fractured limb and the corresponding landmarks for splint measurement. The guide is intended to be a visual aid and comprises mainly of annotated photographs for ease of use. It was made available on the ED intranet, Medical Officer Guidebook and a laminated hard copy was hung at the plaster trolley.

Although we did not meet our target of reducing the rate by 50% due to some challenges, the time and effort invested was minimal given the large impact of reduction in the overall rate of incorrect plaster splints from 84.1% to 68.6%.

The key challenges are Junior Doctors’ incompatible busy work schedule to attend the practical training sessions and some having no knowledge or lack of motivation in learning from the online video lectures available as it can be time consuming. To counter that, our 3rd intervention (Quick Reference Cards) has helped to resolve this issue as they can refer to the resource for guidance at the time when they need to do a plaster splint.

This project is limited in several ways. There was a significant drop in completed survey forms collected in January after the 2nd Intervention, resulting in a falsely high rate of incorrect plaster splints. Our team met the Plaster Room Staff and found that the staff were not motivated in completing survey forms because they were unclear of the effect of their efforts. There was an inherent flaw in methodology used for data collection using the end-user survey. This does not mean our interventions failed to work, it could just be that the plaster cast technician did not collect the data diligently (e.g. only filling up the survey forms for obviously incorrect plaster splints). We then shared our goals and findings to encourage the Plaster Room Staff. Subsequently, the number of completed survey forms started to increase accordingly. The other reason for the sudden increase in error rate after the 2nd Intervention could be that a new batch of Junior Doctors also started their ED rotation in January 2021, which could have resulted in an increased rate of incorrect splints. Generally, Junior Doctors who gets rotated to the ED do not have prior orthopaedic training or postings with no formal teaching on plaster splint applications except during the short exposure in medical school.

Ⅴ. Conclusions

In conclusion, our interventions addressed the incorrect plaster splints by carrying out some formal training for the Junior Doctors in a form of an educational bundle. The benefit from this project was the implementation of the training program and that it has been continued. All new batches of Junior Doctors are made to go through the training and the three sequential interventions are still in practice. This demonstrates the sustainability of our efforts in the ED.

Notes

Funding

None

Conflict of Interest

None